How I failed a startup: A Post-Mortem

This is not the collapse of a million-dollar, venture-backed business – it's the failure of an idea going from "0" to "not 0". Yet, it still taught me lots.

Earlier this year, I launched a startup company called manuAI: a platform for appliance and electronics companies to turn their user manuals into AI customer support. Say your dishwasher is leaking – instead of flipping through the 100-page user manual, you would simply go to the digital manual generated by manuAI, and tell it "my dishwasher is leaking!" It would automatically summarize for you how to fix it, and jump to exactly where to look in the manual.

The vision was to DISRUPT(!!) the appliance industry, saving companies thousands of dollars on customer service and printing costs. You can still see our website and try a demo here: usermanuai.com.

I will spoil the ending: this startup did not make it – it did not die, per se, but both my co-founder and I decided that it was no longer worth working on. As to why it failed, one sentence suffices: we didn't do enough, and we didn't want to do enough. The first part of that sentence is the concrete cause, whereas the latter is the root cause. To understand what we didn't do enough, let’s rewind to the beginning of manuAI.

It was 3 o'clock in a late October morning, I stared at the list of more than 30 ideas I came up with in the last 4 hours, all with a line crossing through them. This was 16 hours before Pitch Night, where I would have to pitch an idea – a good idea – as part of the V1 cohort.

Suddenly, "AI User Manuals" came to my mind – an idea so alluringly good. Running a search on the internet for existing products, I could not find anything: at the peak of the AI-powered, AI-enabled startup frenzy, finding an AI idea that had not been done was, by itself, quite something.

Moreover, I thought this was a real problem – users, like me – would find it more convenient to troubleshoot or learn to use an appliance; thinking from the other perspective, from the companies’ standpoint, they spend a tremendous amount of money on customer service and printing these manuals – this product would eliminate a big chunk of that!

Mistake #1: Don't think a problem is a problem or think that buyers will want to buy your product, consolidate!

Then, after building an MVP and pitching it to the rest of the cohort and some campus-based VC's, we received great feedback, which only fed more into our belief that this could be a legitimately good B2B SaaS company. So before even surveying the industry or talking to any potential buyers, we wanted to perfect the product: adding features, getting it hosted, and setting up analytics.

This was not the way to go – ultimately, we were avoiding the question of "do buyers actually want this?" – instead, we distracted ourselves and convinced ourselves that we were going in the right direction by working on things that did not matter as much.

Mistake #2: Users are the most important variable in the equation.1

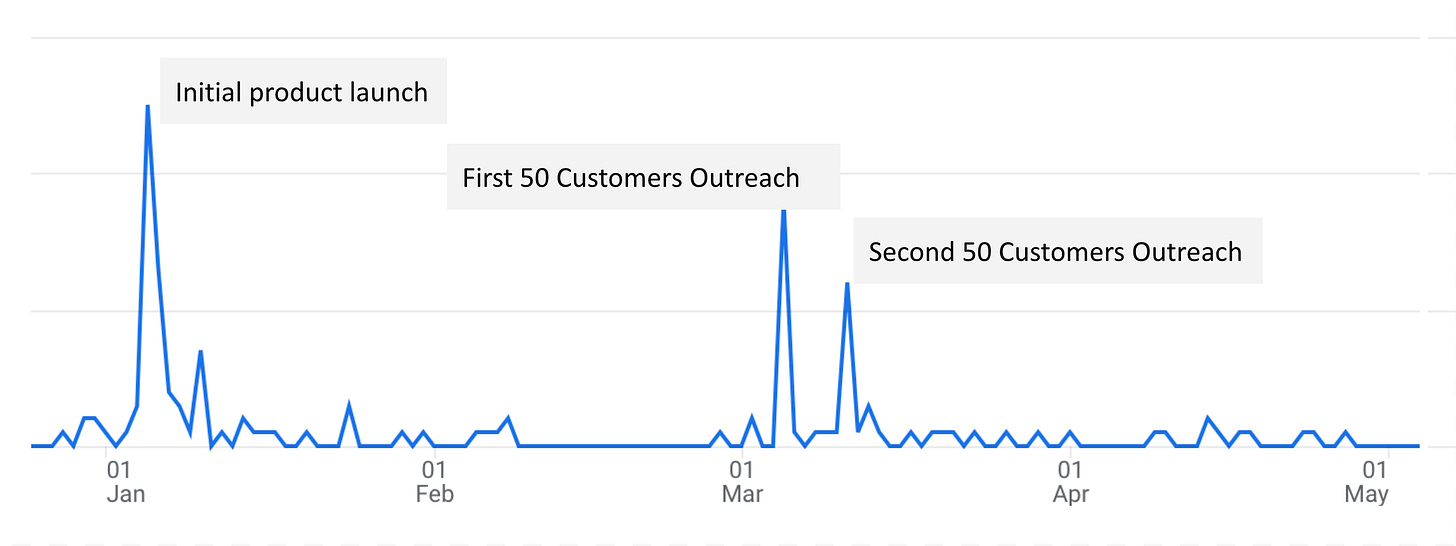

After announcing and launching the product in January to people in various communities, we returned to school as the semester began – the plan was to reach out to potential customers immediately after. However, the start of the semester was hectic, so we indefinitely delayed that – more on that later.

March came around when we finally started reaching out to companies: we found 50 small-medium appliance companies that would need user manuals off PitchBook, and sent an email to all of them with a link to our demo and a Calendly link. One good reply came through after just a few hours – and nil after that. We tried 50 more companies, 0 replies.

With the potential buyer who did reply, we hopped on a call and onboarded them to our product – they were amazed by how easy it was to set up their products' manuals, however, they also expressed pessimism on how many would actually use this, as most of their users are in the age range of > 50. In addition, they spent a bit less than $200 on printing manuals every month, so it was "trivial" – another thing we should've known had we done proper market research. This, alongside long-declining motivation for the both of us, led my co-founder and I to decide that we would not do this anymore.

Looking back, the common theme was we delayed talking to potential users, over and over again – why was this? In my opinion, this reflected that we never had confidence in what we were building:

We did not have evidence that this was a real problem, calling back to Mistake #1.

We did not have any users to tell us whether we are going in the right direction.

Fundamentally, I was not amazed by manuAI as a product – it was a GPT wrapper and anyone could make it. (I don't believe GPT wrappers are intrinsically bad, but, at the time, I was very much affected by the GPT-wrapper-shaming mentality)

Why did this lack of confidence cause the lack of willingness to talk to users? I think it was the fear of rejection and failure: the more unsure we were of our product, the less we want to talk to users who would break to us the hard truth that we were building in the wrong direction. The less we talk to users, the more unsure we were of our product. Thus the vicious cycle begins.

Mistake #3: Do not run yourself into a vicious cycle by building in the dark. Diagnose and admit something is not going to work ASAP!

Mistake #4: Do not build something you don't strongly believe in / have a lot of confidence in.

(This may be specific to me – there are plenty of people who could probably pull off starting something they do not strongly believe in – I don't think I'm one of them.)

To conclude, we didn't do enough – we didn't do proper market research and customer discovery, which led us to a lack of confidence and information. This lack of confidence, together with a fear of rejection and failure, led us to not wanting to do enough. These two factors induced each like Electric and Magnetic fields, and propagated forward with the journey of the startup.

This is definitely not the end of my building and startup career; rather, I think it is a great start – it taught me exactly what to avoid and what not to do. I am sure I will fail many more times in the future – perhaps with even higher stakes! The best thing that could happen after a failure is probably to understand why I failed, and to try to not fail like that again. Anyhow, easier said than done: failure isn’t all rainbow and sunshine after all.

To finish, I would like to thank my co-founder, Johnathan Mo, who was there throughout the life of this venture and put a a lot of thoughts and work into it. I would also like to thank V1 Michigan, without whom I would not have started this project, and everyone who's given us feedback along the way.

This was actually a recurring feedback we got, especially from startup veterans – in hindsight, it was the most valuable feedback and one we should've prioritized over ones about the actual product.

Great reflection - keep building!!

Fun read!